Modelling Change

A really common task in iOS development is to validate input from a form. In this post, I want to look at one possible implementation for doing this by extracting the form validation (business logic) from the view controller. It's not a new concept, but I want to explore how we can leverage Generics and enum associated values to create a graceful and scalable solution.

Well, we can all dream, I guess 😂.

Tweaking your profile

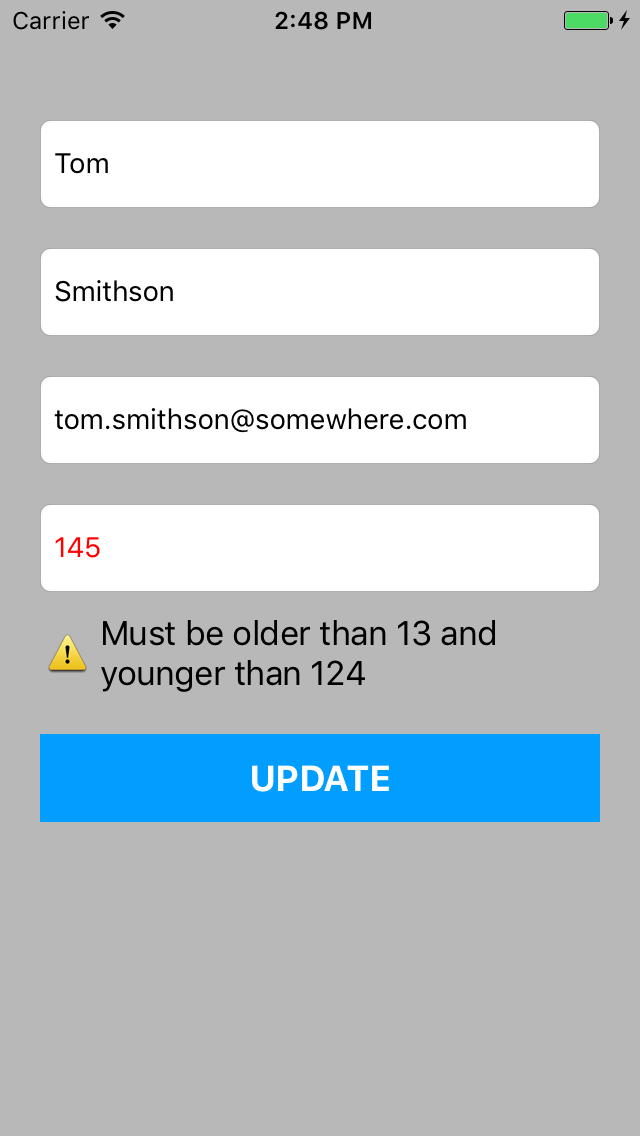

Most of us will have used social media before and so will have created an online profile. Being social creatures, from time to time, we want to change the details on these profiles - we are going to use this edit profile functionality as the basis of this post. Just to give you some eye candy, let's look at the form we will use for editing:

Before we can jump into the code, we need to discuss some of the requirements (business rules) of editing a profile:

- All fields are required

- Firstnames must be at least two characters in length

- Lastnames must be at least two characters in length

- Email addresses must be at least five characters in length

- Age must be between 13 and 124 years old

- Error messages should be shown when any validation rules are broken

- Updating should only occur when the values in the profile have been changed

- Only fields that have changed should be updated

Validating your way to social success 🎉

Okay, so we have our requirements, but before we start building the UI, let's see how we can take those rules and produce a class responsible for enforcing them.

enum ValidationResult<E: Equatable>: Equatable {

case success

case failure(E)

}

func ==<E: Equatable>(lhs: ValidationResult<E>, rhs: ValidationResult<E>) -> Bool {

switch (lhs, rhs) {

case (let .failure(failureLeft), let .failure(failureRight)):

return failureLeft == failureRight

case (.success, .success):

return true

default:

return false

}

}

struct EditProfileErrorMessages: Equatable {

let firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

let lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

let emailLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

let ageLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

}

func ==(lhs: EditProfileErrorMessages, rhs: EditProfileErrorMessages) -> Bool {

return lhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage &&

lhs.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage &&

lhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage &&

lhs.ageLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.ageLocalizedErrorMessage

}

class EditProfileValidator: NSObject {

private let user: User

private var firstNameChanged = false

private var lastNameChanged = false

private var emailChanged = false

private var ageChanged = false

var firstName: String? {

didSet {

firstNameChanged = (firstName != user.firstName)

}

}

var lastName: String? {

didSet {

lastNameChanged = (lastName != user.lastName)

}

}

var email: String? {

didSet {

emailChanged = (email != user.email)

}

}

var age: Int? {

didSet {

ageChanged = (age != user.age)

}

}

// MARK: - Init

init(user: User) {

self.user = user

super.init()

firstName = user.firstName

lastName = user.lastName

email = user.email

age = user.age

}

// MARK: - Change

func hasMadeChanges() -> Bool {

return firstNameChanged || lastNameChanged || emailChanged || ageChanged

}

func changes() -> [String: Any] {

var changes = [String: Any]()

if firstNameChanged {

changes["firstname"] = firstName

}

if lastNameChanged {

changes["lastname"] = lastName

}

if emailChanged {

changes["email"] = email

}

if ageChanged {

changes["age"] = age

}

return changes

}

// MARK: - Validators

func validateAccountDetails() -> ValidationResult<EditProfileErrorMessages> {

var firstNameError: String? = nil

var lastNameError: String? = nil

var emailError: String? = nil

var ageError: String? = nil

switch validateFirstName() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

firstNameError = message

}

switch validateLastName() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

lastNameError = message

}

switch validateEmail() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

emailError = message

}

switch validateAge() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

ageError = message

}

if firstNameError != nil || lastNameError != nil || emailError != nil || ageError != nil {

let editProfileErrorMessages = EditProfileErrorMessages(firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage: firstNameError, lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage: lastNameError, emailLocalizedErrorMessage: emailError, ageLocalizedErrorMessage: ageError)

return .failure(editProfileErrorMessages)

}

return .success

}

func validateFirstName() -> ValidationResult<String> {

guard let firstName = firstName else {

return .failure("Firstname can not be empty")

}

if firstName.characters.count < 2 {

return .failure("Firstname is too short")

} else {

return .success

}

}

func validateLastName() -> ValidationResult<String> {

guard let lastName = lastName else {

return .failure("Lastname can not be empty")

}

if lastName.characters.count < 2 {

return .failure("Lastname is too short")

} else {

return .success

}

}

func validateEmail() -> ValidationResult<String> {

guard let email = email else {

return .failure("Email can not be empty")

}

if email.characters.count < 5 {

return .failure("Email is too short")

} else {

return .success

}

}

func validateAge() -> ValidationResult<String> {

guard let age = age else {

return .failure("Age can not be empty")

}

let minimumAge = 13

let maximumAge = 124

if age < minimumAge || age > maximumAge {

return .failure("Must be older than \(minimumAge) and younger than \(maximumAge)")

} else {

return .success

}

}

}A lot is happening here; however, we can think of it in three sections:

- Data structures to support validation

- Changes

- Validation

1. Data structures to support validation

The data structures are necessary as they allow us to express the outcome of the validation without returning dictionaries or simple booleans.

enum ValidationResult<E: Equatable>: Equatable {

case success

case failure(E)

}

func ==<E: Equatable>(lhs: ValidationResult<E>, rhs: ValidationResult<E>) -> Bool {

switch (lhs, rhs) {

case (let .failure(failureLeft), let .failure(failureRight)):

return failureLeft == failureRight

case (.success, .success):

return true

default:

return false

}

}Here we have an enum ValidationResult which has two values/cases:

- Success

- Failure

The .success case is simple enough; however, .failure has an associated value which we will use for populating the error message when validation fails. We are using generics to allow this enum to be used with different concrete types, the only constraint that we place on those types is that they must conform to the Equatable protocol - in Swift, this form of constraining is called type constraint and could also be used to enforce that the type is of a specific subclass. Generics are used here rather than a concrete type (which would arguably be easier to read), as the .failure case will need to be associated with different types (more on this later). The ValidationResult enum also conforms to Equatable. This is necessary because we don't get equatable checks for free with enums that contain associated values, so we will need to define this behaviour explicitly. The == method under the enum is implementing this equality check. Let's look at EditProfileErrorMessages:

struct EditProfileErrorMessages: Equatable {

let firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

let lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

let emailLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

let ageLocalizedErrorMessage: String?

}

func ==(lhs: EditProfileErrorMessages, rhs: EditProfileErrorMessages) -> Bool {

return lhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage &&

lhs.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage &&

lhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.emailLocalizedErrorMessage &&

lhs.ageLocalizedErrorMessage == rhs.ageLocalizedErrorMessage

}In the above code snippet, we have the EditProfileErrorMessages struct, which will be used to hold the errors returned from our overall form validation check. We could have avoided this struct by choosing to return the error messages in a dictionary; however, then we would have needed to either expose the keys as static values or use magic strings between the validator and any class which used it. EditProfileErrorMessages conforms to the Equatable protocol so that it can be used as one possible associated value for the .failure case.

Validation

Let's look at one of the validation methods:

func validateAge() -> ValidationResult<String> {

guard let age = age else {

return .failure("Age can not be empty")

}

let minimumAge = 13

let maximumAge = 124

if age < minimumAge || age > maximumAge {

return .failure("Must be older than \(minimumAge) and younger than \(maximumAge)")

} else {

return .success

}

}In the above code snippet, we validate that the age value conforms to our business rules. The most interesting part is that we use ValidationResult as our return type. For this method, the ValidationResult instances will use String as it's associated value type. We can see this in action:

return .failure("Must be older than \(minimumAge) and younger than \(maximumAge)")These individual validation checks are then combined in:

func validateAccountDetails() -> ValidationResult<EditProfileErrorMessages> {

var firstNameError: String? = nil

var lastNameError: String? = nil

var emailError: String? = nil

var ageError: String? = nil

switch validateFirstName() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

firstNameError = message

}

switch validateLastName() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

lastNameError = message

}

switch validateEmail() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

emailError = message

}

switch validateAge() {

case .success:

break

case .failure(let message):

ageError = message

}

if firstNameError != nil || lastNameError != nil || emailError != nil || ageError != nil {

let editProfileErrorMessages = EditProfileErrorMessages(firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage: firstNameError, lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage: lastNameError, emailLocalizedErrorMessage: emailError, ageLocalizedErrorMessage: ageError)

return .failure(editProfileErrorMessages)

}

return .success

}In validateAccountDetails, we are also using ValidationResult as the return type, like we did with the validateAge method. However, here we associate the .failure case with EditProfileErrorMessages rather than a String like we did before. It's in this instance that we see the true power of using generics with enums, as it allows us to express two similar but distinct interpretations of failure without polluting our codebase with conceptually-equal enum cases, such as:

enum ValidationResult<E: Equatable>: Equatable {

case success

case firstNameFailure

case lastNameFailure

case emailFailure

case ageFailure

case combinedFailure

}The above enum covers all the cases. As you can see, there are more cases to express failure states than success states. One of the driving forces behind this was also to enable easier unit testing. I won't include them in this post, but if you are interested, head over to the repository and take a look.

Changes

Okay, so that's the validation part of EditProfileValidator, but how do we know if anything has actually changed? We need to track the initial values of each field and then, as it changes, determine if its final state is different from its initial state. The user can edit a field and then revert to its original value, so a simple boolean won't suffice; we need to track its actual value. We could do this by adding a new suite of properties called something like: firstNameInitialValue but we don't need to as we already have the initial values in the User instance that we pass into this class during initialisation - as User is immutable we know that it will contain the values as they were before any editing, we can then use this to determine if any changes have made:

private let user: User

private var firstNameChanged = false

private var lastNameChanged = false

private var emailChanged = false

private var ageChanged = false

var firstName: String? {

didSet {

firstNameChanged = (firstName != user.firstName)

}

}

var lastName: String? {

didSet {

lastNameChanged = (lastName != user.lastName)

}

}

var email: String? {

didSet {

emailChanged = (email != user.email)

}

}

var age: Int? {

didSet {

ageChanged = (age != user.age)

}

}In the above code snippet, you can see that I am utilising didSet to check if the value has changed, and I then store this information in a convenience boolean property. This boolean property isn't strictly necessary, but I feel it improves the readability of the hasMadeChanges method:

func hasMadeChanges() -> Bool {

return firstNameChanged || lastNameChanged || emailChanged || ageChanged

}is clearer than

func hasMadeChanges() -> Bool {

return (firstName != user.firstName) || (lastName != user.lastName) || (email != user.email) || (age != user.age)

}In my opinion, at least 😉.

As we will see in the EditProfileViewController class, this method will be used to determine if we call validateAccountDetails when the user presses the update button. Now we have one more requirement to satisfy, then we can move onto the UI:

Only fields that have changed should be updated

Here we need to assume that the edit profile update process will trigger an API call and send the changes as json, to support this, we want the validator to return a dictionary containing the changes that can then be passed to the API endpoint.

func changes() -> [String: Any] {

var changes = [String: Any]()

if firstNameChanged {

changes["firstname"] = firstName

}

if lastNameChanged {

changes["lastname"] = lastName

}

if emailChanged {

changes["email"] = email

}

if ageChanged {

changes["age"] = age

}

return changes

}In the above code snippet, we check if each field has changed, and if it has, we add a new key-value pair to the changes dictionary.

UI

We've looked at the class that will enforce our business; now we need to look at our view controller:

class EditProfileViewController: UIViewController {

@IBOutlet weak var scrollView: UIScrollView!

@IBOutlet weak var firstNameTextField: UITextField!

@IBOutlet weak var lastNameTextField: UITextField!

@IBOutlet weak var emailTextField: UITextField!

@IBOutlet weak var ageTextField: UITextField!

@IBOutlet weak var firstNameErrorLabel: UILabel!

@IBOutlet weak var lastNameErrorLabel: UILabel!

@IBOutlet weak var emailErrorLabel: UILabel!

@IBOutlet weak var ageErrorLabel: UILabel!

@IBOutlet weak var updateButton: UIButton!

@IBOutlet weak var scrollViewBottomConstraint: NSLayoutConstraint!

lazy var validator: EditProfileValidator = {

let validator = EditProfileValidator(user: self.user)

return validator

}()

lazy var user: User = {

let user = User(firstName: "Tom", lastName: "Smithson", email: "tom.smithson@somewhere.com", age: 27)

return user

}()

// MARK: - ViewLifecycle

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

NotificationCenter.default.addObserver(self, selector: ###selector(keyboardWillShow), name: NSNotification.Name.UIKeyboardWillShow, object: nil)

NotificationCenter.default.addObserver(self, selector: ###selector(keyboardWillHide), name: NSNotification.Name.UIKeyboardWillHide, object: nil)

clearAllErrors()

firstNameTextField.text = user.firstName

lastNameTextField.text = user.lastName

emailTextField.text = user.email

ageTextField.text = "\(user.age)"

}

// MARK: - ButtonActions

@IBAction func updateButtonPressed(_ sender: Any) {

view.endEditing(true)

if validator.hasMadeChanges() {

switch validator.validateAccountDetails() {

case .success:

let alertController = UIAlertController(title: "Save Changes", message: "Can successfully save changes: \n \(validator.changes())", preferredStyle: .alert)

let dismissAction = UIAlertAction(title: "OK", style: .default, handler: nil)

alertController.addAction(dismissAction)

present(alertController, animated: true, completion: nil)

case .failure(let accountValidationErrorMessages):

if accountValidationErrorMessages.firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: firstNameTextField, messagelabel: firstNameErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

if accountValidationErrorMessages.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: lastNameTextField, messagelabel: lastNameErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

if accountValidationErrorMessages.emailLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: emailTextField, messagelabel: emailErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.emailLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

if accountValidationErrorMessages.ageLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: ageTextField, messagelabel: ageErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.ageLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

}

} else {

let alertController = UIAlertController(title: "No Changes", message: "You haven't made any changes to update", preferredStyle: .alert)

let dismissAction = UIAlertAction(title: "Dismiss", style: .default, handler: nil)

alertController.addAction(dismissAction)

present(alertController, animated: true, completion: nil)

}

}

// MARK: - Error

func showError(textField: UITextField, messagelabel: UILabel, message: String) {

textField.textColor = UIColor.red

messagelabel.text = message

messagelabel.superview?.isHidden = false

}

func hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: UILabel) {

messagelabel.superview?.isHidden = true

}

func clearAllErrors() {

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: firstNameErrorLabel)

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: lastNameErrorLabel)

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: emailErrorLabel)

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: ageErrorLabel)

}

// MARK: - Keyboard

func keyboardWillShow(notification: NSNotification) {

let info = notification.userInfo

let rect = (info![UIKeyboardFrameEndUserInfoKey] as AnyObject).cgRectValue

let duration = (info![UIKeyboardAnimationDurationUserInfoKey] as AnyObject).doubleValue

let option = UIViewAnimationOptions(rawValue: UInt((notification.userInfo![UIKeyboardAnimationCurveUserInfoKey]! as AnyObject).integerValue << 16))

UIView.animate(withDuration: duration!, delay: 0, options: option, animations: {

let keyboardHeight = self.view.convert(rect!, to: nil).size.height

self.scrollViewBottomConstraint?.constant = keyboardHeight

self.scrollView.layoutIfNeeded()

}, completion: nil)

}

func keyboardWillHide(notification: NSNotification) {

let info = notification.userInfo

let duration = (info![UIKeyboardAnimationDurationUserInfoKey] as AnyObject).doubleValue

let option = UIViewAnimationOptions(rawValue: UInt((notification.userInfo![UIKeyboardAnimationCurveUserInfoKey]! as AnyObject).integerValue << 16))

UIView.animate(withDuration: duration!, delay: 0, options: option, animations: {

self.scrollViewBottomConstraint?.constant = 0

self.scrollView.layoutIfNeeded()

}, completion: nil)

}

// MARK: - Gesture

@IBAction func backgroundTapped(_ sender: Any) {

view.endEditing(true)

}

}

extension EditProfileViewController: UITextFieldDelegate {

// MARK: - UITextFieldDelegate

func textFieldDidBeginEditing(_ textField: UITextField) {

textField.textColor = UIColor.black

scrollView.setContentOffset(CGPoint.init(x: 0, y: textField.superview!.frame.origin.y), animated: true)

}

func textFieldDidEndEditing(_ textField: UITextField) {

if textField == firstNameTextField {

validator.firstName = textField.text

switch validator.validateFirstName() {

case .success:

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: firstNameErrorLabel)

break

case .failure(let localizedErrorMessage):

showError(textField: textField, messagelabel: firstNameErrorLabel, message: localizedErrorMessage)

}

} else if textField == lastNameTextField {

validator.lastName = textField.text

switch validator.validateLastName() {

case .success:

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: lastNameErrorLabel)

break

case .failure(let localizedErrorMessage):

showError(textField: textField, messagelabel: lastNameErrorLabel, message: localizedErrorMessage)

}

} else if textField == emailTextField {

validator.email = textField.text

switch validator.validateEmail() {

case .success:

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: emailErrorLabel)

break

case .failure(let localizedErrorMessage):

showError(textField: textField, messagelabel: emailErrorLabel, message: localizedErrorMessage)

}

} else if textField == ageTextField {

var age = "0"

if textField.text != nil {

age = textField.text!

}

validator.age = Int(age)

switch validator.validateAge() {

case .success:

hideErrorMessage(messagelabel: ageErrorLabel)

break

case .failure(let localizedErrorMessage):

showError(textField: textField, messagelabel: ageErrorLabel, message: localizedErrorMessage)

}

}

}

func textFieldShouldReturn(_ textField: UITextField) -> Bool {

if textField == firstNameTextField {

lastNameTextField.becomeFirstResponder()

} else if textField == lastNameTextField {

emailTextField.becomeFirstResponder()

} else if textField == emailTextField {

ageTextField.becomeFirstResponder()

} else {

ageTextField.resignFirstResponder()

}

return true

}

}Another sizable code drop, but we won't go through all of it; instead, we will focus on the more interesting parts.

Yes, the 'age' field would be safer as a

UIPickerView, but implementing that goes outside of the scope of this post.

lazy var validator: EditProfileValidator = {

let validator = EditProfileValidator(user: self.user)

return validator

}()Here we lazy load the validator that we explored above. In this case, I have used lazy loading as a design approach to separate the initialisation of properties. There is no meaningful performance gain here, and this could easily have been initialised in viewDidLoad.

lazy var user: User = {

let user = User(firstName: "Tom", lastName: "Smithson", email: "tom.smithson@somewhere.com", age: 27)

return user

}()We need a User instance to populate the edit profile, so we are lazy loading it here. Typically, a User instance would be passed into this view controller using dependency injection to allow us to test this class more easily. The next really interesting part is what happens when the user presses that "Update" button:

@IBAction func updateButtonPressed(_ sender: Any) {

view.endEditing(true)

if validator.hasMadeChanges() {

switch validator.validateAccountDetails() {

case .success:

let alertController = UIAlertController(title: "Save Changes", message: "Can successfully save changes: \n \(validator.changes())", preferredStyle: .alert)

let dismissAction = UIAlertAction(title: "OK", style: .default, handler: nil)

alertController.addAction(dismissAction)

present(alertController, animated: true, completion: nil)

case .failure(let accountValidationErrorMessages):

if accountValidationErrorMessages.firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: firstNameTextField, messagelabel: firstNameErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.firstNameLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

if accountValidationErrorMessages.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: lastNameTextField, messagelabel: lastNameErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.lastNameLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

if accountValidationErrorMessages.emailLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: emailTextField, messagelabel: emailErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.emailLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

if accountValidationErrorMessages.ageLocalizedErrorMessage != nil {

showError(textField: ageTextField, messagelabel: ageErrorLabel, message: accountValidationErrorMessages.ageLocalizedErrorMessage!)

}

}

} else {

let alertController = UIAlertController(title: "No Changes", message: "You haven't made any changes to update", preferredStyle: .alert)

let dismissAction = UIAlertAction(title: "Dismiss", style: .default, handler: nil)

alertController.addAction(dismissAction)

present(alertController, animated: true, completion: nil)

}

}Due to the scope of this example, I didn't implement an actual API call (which would be in a separate class); instead, I display an alert with the changes. The first thing this method does is check if any changes have actually been made. If changes have been made, we then verify if those changes are valid. If not, we display error messages under the text fields detailing what went wrong.

Thinking about alternatives

One alternative I explored was using simple Boolean returns to indicate failure; however, this doesn't work with the level of detail we need for the failures in validateAccountDetails. The other alternative, which had more merit, was throwing errors. This approach works well, but I chose the enum approach because the level of boilerplate code required to set up the throwing approach obscured the purpose of the validator, making the project harder to understand.

🤔

Looking back

There is a lot of code in this post that isn't directly related to validation; I included it to illustrate more clearly how this approach can be applied to a semi-realistic form. However, the beauty of this approach is that we now have a class that is independent of the UI. This separation results in the business rules being easier to unit test, as we no longer need to set up the UI to test them. It also ensures that the view controller has more cohesion as it's really only dealing with manipulating the view.

To see the above code snippets together in a working example, head over to the repository and clone the project.