Leveraging Single-Responsibility Principle to Find Hidden Modules

Single-Responsibility Principle (SRP) is a concept most developers encounter early in their pursuit of maintainable code. It states that any unit of work in your system should serve a single purpose. It's a powerfully simple idea that has found widespread adoption.

Most examples of SRP focus on methods or classes. But the principle is broader than that: SRP is about how we organise the ideas that make up our projects. And that same focus can - and should - apply to larger units such as modules or libraries.

In this post, we'll explore how applying SRP at the project level allows us to split a single monolithic module into separate, more focused modules, and how that separation leads to more adaptable, maintainable apps.

Why Focus Matters

When everything lives inside a single, monolithic module, boundaries blur and small changes ripple unpredictably. By applying SRP at the module level, you carve out more focused areas of functionality.

This increased focus pays off in several ways:

- Sets clearer boundaries - Safer refactoring, fewer leaks of internal details, and bugs that stay contained.

- Better flexibility - Features can grow or change without disturbing the rest of the app.

- Allows parallel working - Teams can develop independently with fewer merge conflicts.

- Improves reusability - Well-named modules are easier to discover and reuse, preventing duplication.

- Lowers cognitive load - You only need to know what a module provides, not how it works.

- Enables faster debugging & testing - Failures are easier to isolate, and tests are more focused.

However, that increased focus isn't free; it incurs additional costs:

- Upfront effort - Deciding where to draw boundaries takes time. Do it badly, and you risk creating more tangles than you remove.

- More moving parts - Every new module adds setup, dependencies, and build steps. For small teams or projects, that ceremony can feel like overkill.

- The risk of going too far - Split too aggressively, and you end up with a forest of “nano-modules” that are harder to navigate than the monolith you started with.

- Some changes are more expensive - Once you've published a module, changing its public API isn't simple - you now need to coordinate with every team or feature that depends on it.

Like any design choice, modularisation buys you flexibility at the cost of complexity. The key is not to chase perfection, but to find the level of focus that makes your project easier, not harder to work with.

Finding Focus

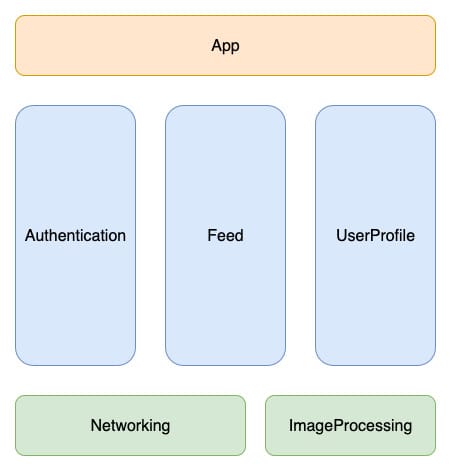

If your project is monolithic, deciding where to start modularising can feel overwhelming. Following SRP, each module should have a single focus. The task is to identify those areas of focus, which are usually either technical (like networking or data storage) or feature (like user profiles or feed) in nature. Technical modules serve as building blocks that multiple features depend on, while feature modules typically stand alone.

Spotting hidden modules - especially the first one - can be tricky. Here are some useful heuristics to help you:

- Look for grouped functionality - high cohesion within a group of functionality is a strong signal of a hidden module.

- Identify technical modules before feature modules - technical functionality tends to be more isolated because multiple features already share it.

- Start at the bottom of the dependency chain - functionality with fewer dependencies should be easier to spot and extract.

- Zoom out with a diagram - sketch a quick diagram of the project’s functionality and see what groupings jump out. Don’t overthink it - aim for broad blocks, not fine detail.

In practice, these heuristics often reveal natural boundaries, for example:

If you are unsure about whether functionality is a hidden module or not, leave it - extract the modules that do jump out at you and reassess once the current module is smaller.

Once you've identified a hidden module, pull it into its own module using this two-stage approach:

- Extract - Move the existing functionality, as is, into a new module.

- Refactor - Improve the focus of the new module.

Stage 1: Extract

If you haven't already done so, convert your project into a workspace to allow for those modules to be split out, then re-wired back in. Details of how to do that can be found here.

- Create a new framework project and add it to your workspace.

- Add the new framework as a dependency for any projects in the workspace that need the functionality you are about to move.

- Move all related functionality into the new module, including both production and test code.

3.1. Fight the urge to refactor at this stage - extraction is already a big enough change. - Review the code and expose only the functionality that’s actually used elsewhere.

- Update any implicit dependencies to make them explicit.

5.1. Do only the minimum required to get the project compiling. - Integrate the new module back into the places where its functionality was originally used.

See

Hitting the Target with TestHelpersfor details about how you can share test doubles between modules.

Even without changing a line of logic, you'll notice the benefits: clearer boundaries, lower cognitive load, and a project that already feels easier to reason about.

Now it's time to move on to the second stage.

Stage 2: Refactor

During extraction, you likely noticed areas for improvement in the newly separated code. The refactoring stage is where you address these issues:

- Start with API-affecting changes first - Minimise disruption by getting interface changes done early, before your teammates build dependencies on temporary APIs.

- Work incrementally - Split refactoring into small tasks and let each completed task guide the next. No need to have all the answers upfront.

- Offload misplaced functionality - Remove code that doesn't belong (e.g., UI code in a networking module) to sharpen the module's focus.

- Decouple dependencies - Use patterns like delegation and closures to break ties to functionality now living in other modules.

- Remove unused frameworks - This is good housekeeping, but also creates wanted friction against adding inappropriate functionality later. This additional friction should act as a reflection point for the developer to question if the functionality really belongs in that module.

Every change has a grace period where teammates will tolerate disruption. Use that time wisely, focus on sharpening the module's purpose rather than chasing perfection. Set yourself up for success, not failure, by not being too ambitious here - you can always come back later and refactor in waves.

Now that you've extracted and refactored your first module, repeat the process with the other hidden modules you identified.

Extraction and refactoring give you focused modules. The next challenge is keeping them that way.

Keeping Focus

Now that you have modules in your project, you have to maintain them. Modules are only as good as they are focused. The more focused a module is, the better it operates as a module. So we need to keep it that way. Not to get too John Proctor on you, but there is power in a name. The name of the module is your best defence in keeping a module focused.

Avoid vague names, like:

- Core - Could contain anything from networking to UI utilities.

- Common - Equally vague, invites dumping ground behaviour.

- Shared - Doesn't indicate what's being shared or why.

- Utils or Helpers - These are code smells at the module level.

Instead, use focused names like:

- Networking - Clear technical focus.

- Authentication - Specific feature responsibility.

- ImageProcessing - Well-defined domain.

- UserProfile - Clear feature boundary.

A module's name acts as a cognitive gate - when someone wants to add functionality, they have to justify why it belongs in Networking rather than just tossing it into Core. A focused name creates friction that protects the module's boundaries. If a module starts to grow such that the name no longer contains the functionality it has, well, that's a code smell that that module needs to be separated into smaller modules to regain focus.

Before settling on a name, ask: "If a developer unfamiliar with this codebase saw this module name, would they correctly guess what belongs in it and what doesn't?" If the answer is no, keep refining.

Turning Focus into Speed

As a project grows, the weight of a single module can slow everything down. By applying the SRP not just to classes but to modules, we turn a monolith into a collection of smaller, more-focused parts. Each module does one thing, does it well, and makes the whole system easier to change.

Focused modules restore the speed and clarity of working small, even as the project grows large.